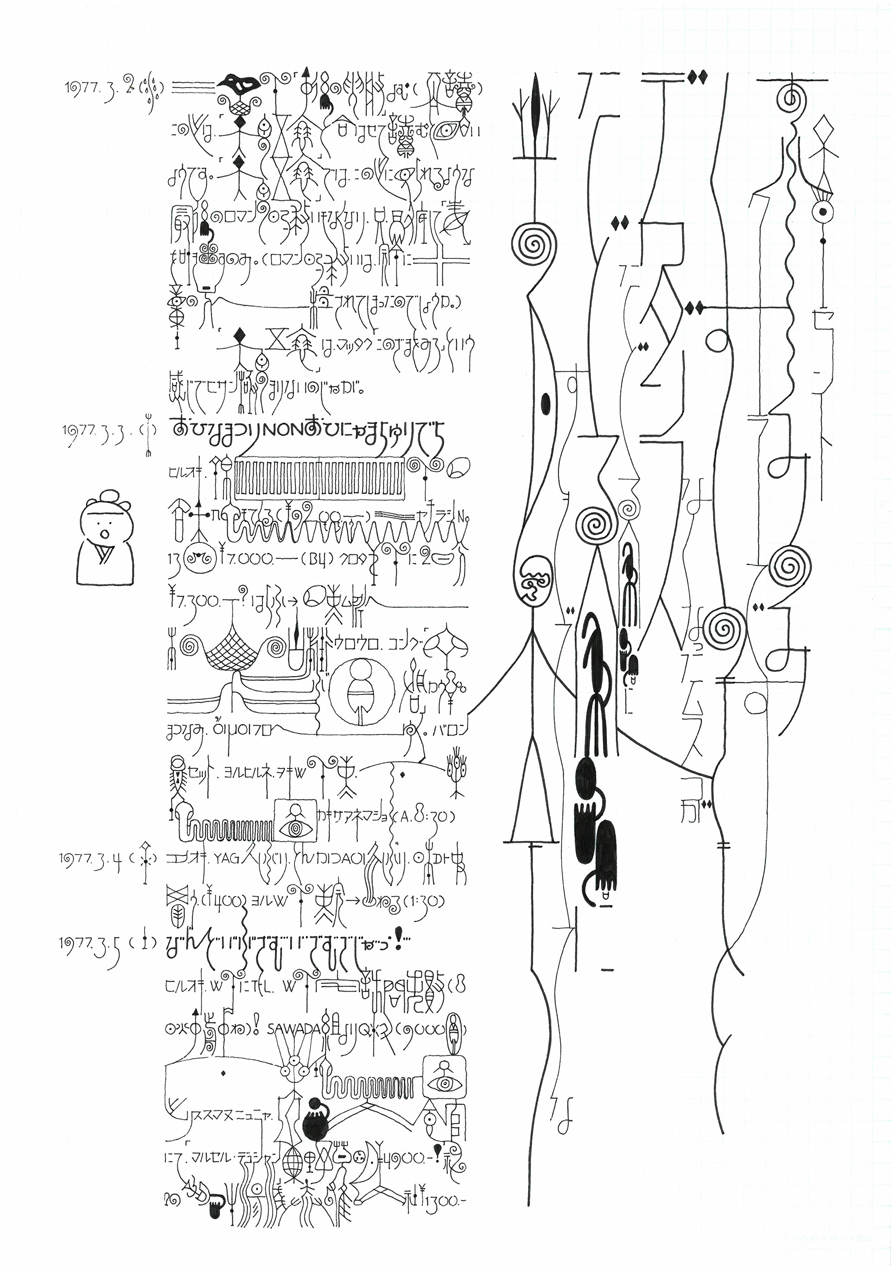

紙にインク, 210mm × 297mm, 2002年 / Ink on Paper, 210mm × 297mm, 2002.

三島由紀夫の小説は、学生時代にかなり読んだ。『午後の曳航』は、この頃、日米合作映画で公開されたので再読。三島さんの文章は、ぎちぎちと妥協を許さずに書きこんでいくタイプで、執筆には相当のエネルギーが要りそう。霞で遠近感をごまかす?日本画風の曖昧模糊とした表現ではなく、目に見えるものすべてをぎっちりと描きこんでいく細密の油絵風の文体が、西洋語には載りやすく、早くから外国で人気が出た要因の一つだったのではないかと思われる。そのエネルギーは結局劇的な自己完結の道を辿ったが、日本語で書く作家としては、やはり特異な存在だったのではないだろうか。『文章読本』などを見ると、本人は、自分の文体について、けっして満足しておられなかったようだが……。

I considerably read a novel of Yukio Mishima for school days. Because his "The Sailor Who Fell from Grace with the Sea" was filmized by Japan-U. S.collaboration these days, and was shown in Japan, I read this novel again. His sentence seems to need considerable energy to write, for a type of writing in without permitting compromise in detail. Because his writing style is not the Japanese painting-like one that deceives the perspective by using haze, but is the european minute oil painting-like one that pictures visible everything in closely, his novels are easy to translate into any Western language. I think this is one of the reason that his novels are accepted wholly from his early times at foreign countries. His overflowing energy led himself to that dramatic ultimate, but, I think his sentences have still a monolithic position in Japanese literature. But it seems that he didn't satisfy about his own sentence, as his essay, "Bunshou-Tokuhon"(how to write literatures).